As food consumers we are bombarded by meal deals (for our lunchtime sandwich or for that special 3 course evening meal) and multi-buy deals (e.g. BOGOFs or 3 for £5 etc). The focus on the cost of sustaining ourselves is very real given recent food price inflation – and for many a costly monthly outgoing.

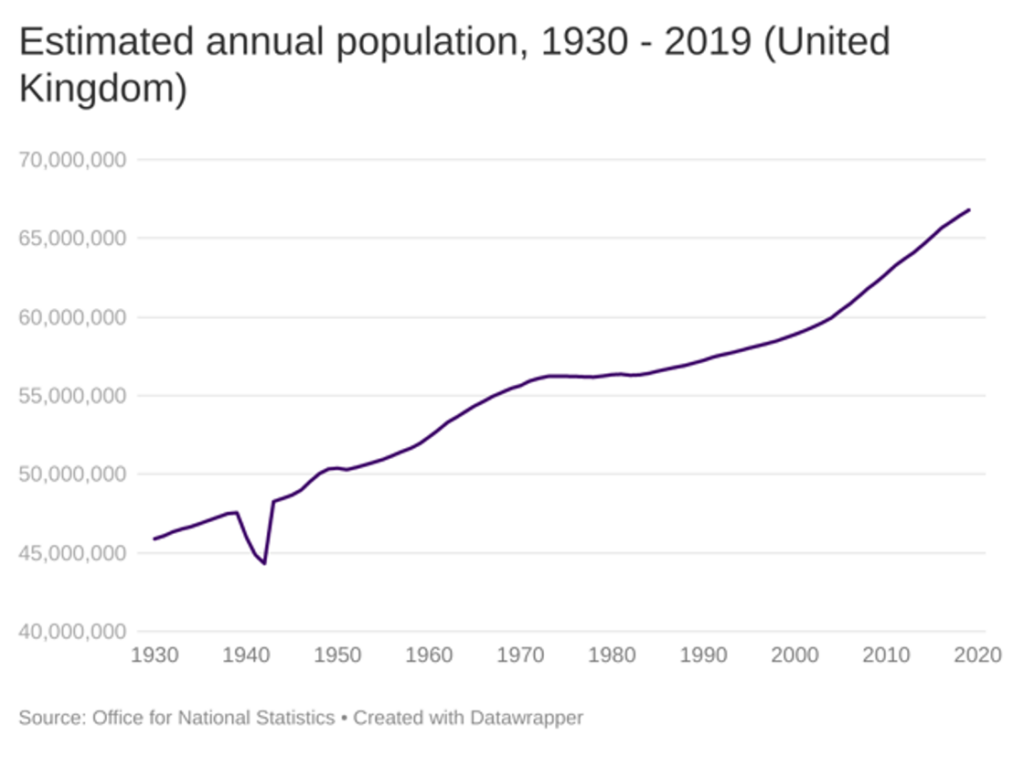

Since the end of WWII there has been a significant focus on increasing domestic food production; at the same time our population has almost doubled. The following two graphs demonstrate this:

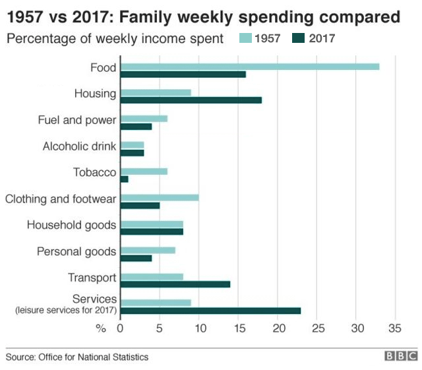

During this time the focus was not just on improving yields but also reducing the cost of food. Consequently, the proportion of household income spent on food has declined (see graph below) by almost half and is now the third lowest in the world.

Whilst these trends are oft repeated, given there has been much focus recently on the UK being one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world, these statistics are worth revisiting.

Demands for increased domestic production post WWII resulted in land use change and management intensification with Government grants (for drainage for example) and agri-tech developments allowing the economically viable growing of arable crops on previously marginal land and higher stocking rates on improved pastures. The focus on food security was not surprising and the unintended consequences of these developments’ unknown at the time. The Common Agricultural Policy was another incentive to intensify production.

The true cost therefore of our meal deal is not just its production cost. The unintended consequences of our food production industry are increasingly being understood as we learn the impacts of this system on soil health, animal welfare, biodiversity, water and air quality, greenhouse gas emissions and other ecosystem goods and services.

So, we are faced with a conundrum – if we account for the true cost of food then more and more low-income families will face food poverty and quite possibly health impacts due to reducing their consumption of more costly fresh fruit and vegetables and increasing consumption of cheap ready meals. But if we intensify to reduce food costs we risk impacting our wildlife and other natural assets such as water.

Last year Henry Dimbleby produced his National Food Strategy which sought to consider the food system as a whole – “from farm to fork” – and put forward a number of recommendations to address the negatives and put our food system on the right footing in terms of resilience to supply shocks and climate change, and supporting health whilst meeting high standards of production. The Government has yet to fully respond. It is interesting that this report was commissioned after four policy outcomes that are integral to food production – the 25YEP, the industrial strategy, Agriculture Act and Environment Bill (now Act); does this signal that this is the order of priorities for this Government? In addition, viewing these policy outcomes individually rather than as part of a holistic approach risks misjudgements in trade-offs between the outcomes. How our land is managed may end up being one of the unintended trade-offs.

A recent debate in Westminster Hall advocated the role that sustainable intensification should play in addressing both food security and biodiversity. The scientific evidence that supports this approach was funded by a Defra project of which the GWCT was a part. However as Julian Sturdy MP, who brought the debate reflected, the outcomes of this research do not appear to be embedded in the current direction of travel for agricultural policy. Current emphasis seems to be on extensification whilst the weight of scientific evidence points to a need to optimise production on existing farmland whilst other land is set aside for nature. This can be in the same field and certainly on the same farm.

The food versus biodiversity debate will continue as we consider the future of our landscape. We are realistic enough to know that Government needs to balance all the demands made on our land; a hundred years ago arguably there were only 5 – food, forestry, industry, transport and housing – now there are these plus the key 25 YEP objectives of biodiversity, net zero, leisure and recreation, health and wellbeing, hazard mitigation, water quality and air quality. To bring all these demands together suggests the need for an England land-use strategy[1] that will identify how to ‘stack’ these demands and balance the inevitable trade-offs. We welcome the setting up of the House of Lords select committee on Land Use in England and look forward to learning of their conclusions.

[1] National Food Strategy: The plan – recommendation 9 Create a Rural Land Use Framework based on the three compartment model.