The recent People’s Trust for Endangered Species/British Hedgehog Preservation Society report on the State of the British Hedgehogs 2022 makes mixed reading. The population and distribution picture for hedgehogs is compiled from a number of different surveys addressing different objectives (e.g. British Trust for Ornithology Garden BirdWatch) – there is no dedicated hedgehog survey or indeed a standard methodology for recording hedgehogs. These surveys however do identify common trends – the decline in overall numbers, the relative improvement in urban populations and the continuing decline in rural areas.

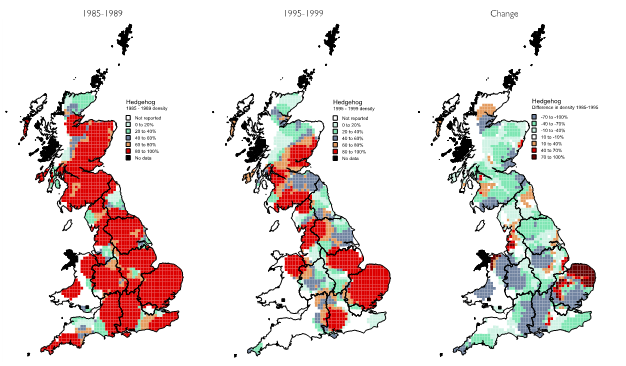

One of the surveys that contributed data was the GWCT’s National Gamebag Census (NGC) (see figure below showing regional trends in relative hedgehog abundance 1985-1999).

Contributions to the NGC are voluntarily submitted by shoots and are not random but they are a useful source of data from the open countryside. The NGC and the mammal recording done in the BTO Breeding Bird Survey showed a degree of concordance between schemes in geographical patterns, and in broad rather than fine-scale patterns across all mammals surveyed [1]. For hedgehogs, the NGC (as opposed to the BTO survey) was able to identify regional declines in abundance in the East Midlands and East Anglia, with too few sites in other areas to generate trends.

It is worth bearing in mind that the NGC data is a by-product of trapping practices, which have become more target selective over time. This effect would have been felt across the country, however, so is unlikely to have resulted in regional trends. It is also possible that the management on NGC sites may be a contributing factor to reported abundance. Shoots are known to maintain more established woods and plant new woods and hedgerows[2] and undertake predator control, in support of good gamebird management, which in turn provides food resources, shelter and breeding requirements (and protection from predators) for a number of other species.

The Trust produced a thorough examination of the causes of hedgehog decline in December 2021 (see Badgers and hedgehogs briefing sheet) so I don’t intend to revisit the science. Instead, what the PTES/BHPS report shows is that hedgehog conservation needs a consensus approach that considers all possible causes of hedgehog decline identified by the science.

The evidence points to a number of causes in rural areas and so any conservation strategy would be incomplete without addressing all of them. Whilst badger presence can be an important factor in hedgehog presence at a local scale, given that they are the only true predator of the hedgehog, other factors such as good habitat and food availability are much stronger predictors. Consequently, habitat loss and fragmentation and invertebrate declines are also important. In addition, road networks (and increased traffic movements) and climate change are major threats to hedgehogs.

In theory it is quite easy to address the need for more appropriate habitat and to look to management that improves food sources such as earthworms. Given that both hedgehogs and badgers share similar habitats and food sources these actions could create the ideal conditions whereby there is sufficient resource to support both species. However, as our Allerton project shows this is not always enough.

At Allerton we have good habitat that in theory would support hedgehogs – as evidenced by record levels of moths, songbirds and badgers but none of our scientists undertaking biodiversity counts has seen a hedgehog for a decade. Given that ground nesting birds are also suffering there is an inference here that badger predation could be a factor in both declines. Indeed, other research has shown that badger presence drives hedgehogs towards rural villages – and urban centres – where food availability is also higher.

In addition, the decline in hedgehog densities identified in our NGC data coincides with an increase in the numbers of badgers across Britain[3] – and indeed it is probably not coincidence that with 55% of the estimated badger population in England and Wales in the south-west of England and south Wales[4], these areas were among the first where hedgehogs ceased to be reported to the NGC.

Data from areas where badgers are culled for tuberculosis could be used to provide evidence of any response from remaining hedgehog populations. There are anecdotal reports of some level of recovery from badger cull areas and Trewby et al (2014)[5] investigated this. The study found that hedgehog numbers increased significantly in grassland areas although it was not clear if this was because of changes in hedgehog behaviour rather than increases in numbers due to reduced predation (threatened or actual), or less competition for food, or some combination. This might indicate that where hedgehog numbers have fallen to unsustainable levels, some form of badger control alongside habitat provision would be appropriate. Then, once hedgehog populations have recovered to levels that can withstand predation, culling would cease.

Harder to assess are the impacts of climate change on habitat and food availability (although the research in the Hebrides suggested climate warming might increase their range) and so any conservation strategy needs to be adaptable with on-going research into the causes of declines and possible mitigation strategies. Research on the impact of reduced tillage and direct drilling in arable fields at our Allerton R&D farm has shown that earthworm numbers leapt from around 200 per m square up to 700 m2 after a single rotation. After a rain shower one night the game keeper counted 26 badgers feeding on earthworms in the field, but no hedgehogs.

To save the hedgehog, epitomised as Mrs Tiggywinkle from our childhood, we need regular national surveys to provide good quality data at all scales and in all landscapes and a holistic conservation strategy that addresses the relevant causes of decline in different regions.

- Noble, D.G., Aebischer, N.J., Newson, S.E., Ewald, J.A. & Dadam, D. (2012) A comparison of trends and geographical variation in mammal abundance in the Breeding Bird Survey and the National Gamebag Census JNCC Report No. 468

- Oldfield, T.E.E., Smith, R.J., Harrop, S.R. & Leader-Williams, N. (2003). Field sports and conservation in the United Kingdom. Nature 423: 531-533.

- Sainsbury, K.A., Shore, R.F., Schofield, H., Croose, E., Campbell, R.D. & McDonald, R.A. (2019). Recent history, current status, conservation and management of native mammalian carnivore species in Great Britain. Mammal Review 49: 171-188.

- Judge, J., Wilson, G.J., Macarthur, R., McDonald, R.A. & Delahay, R.J. (2017). Abundance of badgers (Meles meles) in England and Wales. Scientific Reports 7(276): 1-8.

- Trewby ID, Young R, McDonald RA, Wilson GJ, Davison J, Walker N, et al. (2014) Impacts of Removing Badgers on Localised Counts of Hedgehogs. PLoS ONE 9(4): e95477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095477